Gold, Sanctions, and the New AML Frontier

How untraceable metal became the new language of risk — and why compliance is catching up.

Gold doesn’t confess. It melts, reforms, and forgets. And in a world obsessed with traceability, that forgetfulness has become a business model.

As sanctions multiply and digital transactions become easier to monitor, value is quietly flowing back into the oldest asset class on earth. From Mali’s artisanal pits to Dubai’s refineries and Istanbul’s free-trade zones, gold has become the preferred store of wealth for sanctioned states, private militias, arms brokers, and politically exposed elites looking to move assets beyond the reach of Western oversight. It’s not just a hedge against inflation — it’s an escape route from financial surveillance.

The Perfect Laundering Metal

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and Egmont Group’s report on Trade-Based Money Laundering: Trends and Developments notes that high-value, low-volume commodities such as gold have become one of the most efficient ways to move value covertly. The reasons are straightforward: gold is portable, universally liquid, and its physical transformation erases its past.

A tonne of gold is worth more than US $130 million and can fit inside a briefcase and cross borders silently. Once melted, its origin vanishes.

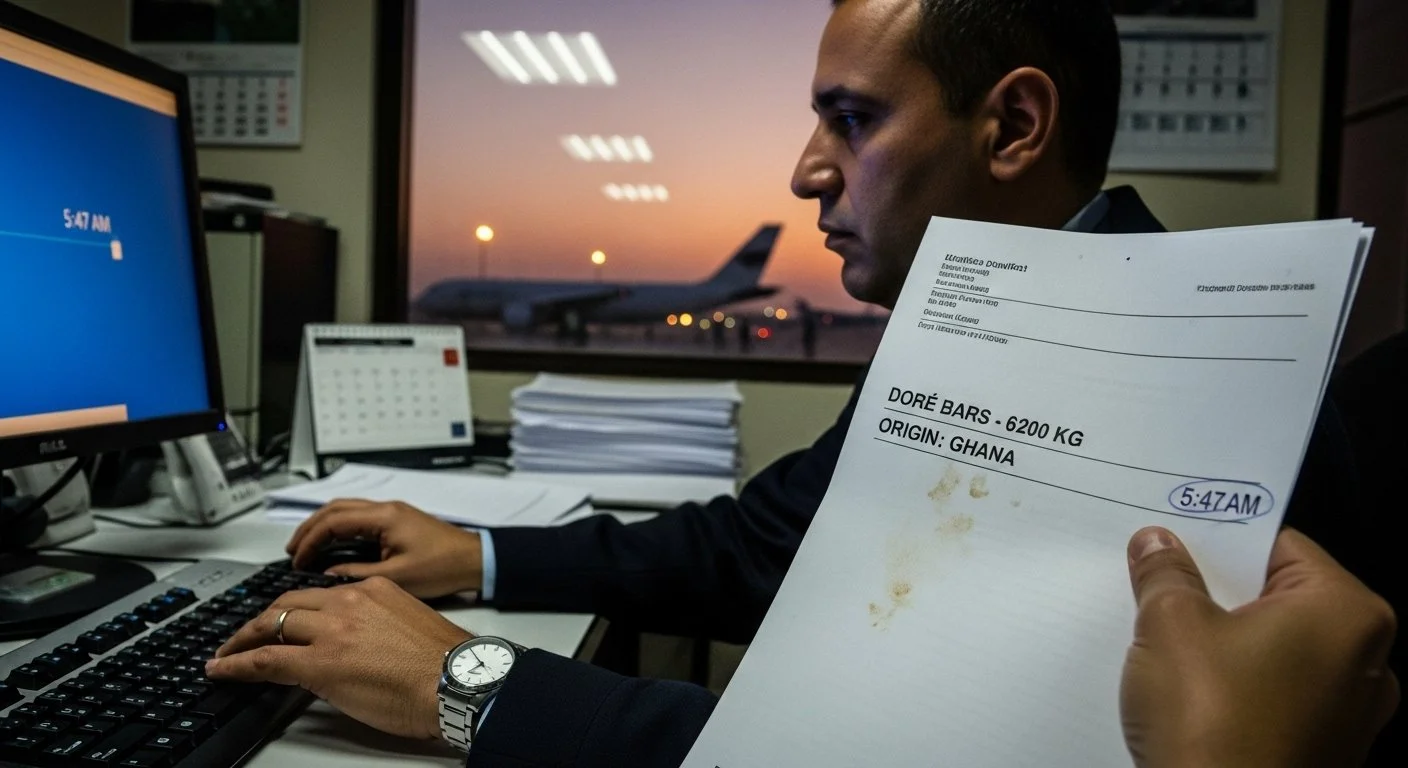

Investigations by Swissaid and Reuters show how easily this happens. Up to 435 tonnes of African gold—worth roughly US $31 billion—were smuggled to the UAE in 2022 alone, much of it from Mali and Sudan. Once in Dubai, the doré is refined, re-stamped, and exported again as clean bullion.

Even the UAE’s own Dealers in Precious Metals and Stones report (2025) acknowledges the problem, rating the sector “medium to high risk” for money laundering and smuggling. Refineries are required to maintain documentation proving ethical sourcing—but the process often relies on self-declared paperwork rather than independent verification.

In practice, this means a doré bar can pass through three jurisdictions and multiple intermediaries before emerging as “clean.” By the time it reaches a major market, its past has been melted away.

From Sanctions Evasion to Systemic Risk

What began as sanctions evasion has evolved into a parallel financial system. Every tonne of untraceable gold entering legitimate supply chains doesn’t just fund conflict or criminal networks—it also distorts markets. By inflating the visible global supply, illicit refining quietly erodes confidence in “paper gold” derivatives.

Meanwhile, physical demand is surging. Bullion dealers from Sydney to Singapore report queues around the block as investors seek tangible assets amid economic uncertainty. The more digital finance becomes, the more people crave the physical. You can manipulate data; you can’t counterfeit weight.

In an era of algorithmic trust and synthetic value, gold’s tangibility feels like certainty.

The Compliance Paradox

Even Bitcoin leaves a trail. Every token transfer is timestamped, verified, and auditable. What once looked like a criminal’s dream has become one of the most traceable financial systems on earth. Regulators have already absorbed blockchain analytics into mainstream compliance — from New York’s Department of Financial Services to the UAE’s virtual-asset regulator.

Gold, by contrast, lives outside that architecture. Once melted, it forgets everything. Yet the same digital tools that now safeguard crypto transactions could be adapted to track physical commodities. Blockchain-based provenance records, tamper-proof assay certificates, and serialised logistics data could create a digital shadow for every shipment of metal.

The technology exists. What’s missing is the incentive to use it.

The New AML Frontier

The FATF’s Guidance on the Risk-Based Approach for Dealers in Precious Metals and Stones and the OECD’s due-diligence framework for responsible mineral supply chains both point toward the same conclusion: gold traders should be treated like financial institutions in practice, even if they’re categorised as “Designated Non-Financial Businesses and Professions” in law.

That means more than collecting supplier forms — it means verifying ownership structures, screening intermediaries, and filing suspicious transaction reports through national FIUs just as banks do. The UAE’s FIU DPMS Sector Analysis shows this is feasible, with hundreds of dealers now integrated into goAML and subject to thematic inspections.

Refiners are the next frontier. To end “paper compliance,” LBMA accreditation could evolve toward evidence-based verification: randomised upstream audits, trace-element testing for origin plausibility, and public reporting of country-of-mine data. The LBMA’s Responsible Gold Guidance v9 (2024) already nudges in that direction; enforcement will decide whether it matters.

The real innovation will be technical. Gold needs a digital memory — a persistent record that survives the melt.

Tamper-evident RFID seals, digital assay certificates, and shipment hashes could be registered to an open provenance ledger, linking every new bar to its original doré. Combined with trade-based money-laundering analytics — monitoring for abnormal invoice values, repeated use of free-trade zones, and suspicious round-tripping — this would make gold traceable enough to deter abuse without paralysing legitimate trade.

In short: the New AML Frontier for gold isn’t about new laws. It’s about connecting existing ones — merging digital-asset surveillance, trade-finance intelligence, and physical-supply-chain due diligence into one unified visibility layer.

That’s the intersection where Anqa lives: building systems that make transparency scalable — and forgetting expensive.

Further Reading

FATF–Egmont: Trade-Based Money Laundering – Trends and Developments (2020)

FATF: Guidance on the Risk-Based Approach for Dealers in Precious Metals & Stones (updated)

Reuters: Gold worth tens of billions smuggled to the UAE each year (2024)

UAE FIU: Dealers in Precious Metals and Stones Report (2025)

OECD: Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Mineral Supply Chains

The Gold Curtain: Inside the global escape plan from the US dollar (2025)